Why did I create a custom application to pattern Airform membranes?

Imagine creating a wedding dress for a bride you never meet. With only two or three measurements, you design the dress, make a pattern, cut the fabric, sew it together, box it up, and ship it to her — hundreds of miles away. She isn’t allowed to wear the dress until the wedding day. Then, at the altar, with her friends and family watching, she puts it on. Will it fit? Will she love it?

That’s what it’s like to manufacture a Monolithic Dome Airform membrane — the key technology of Monolithic Dome construction. Weeks or months earlier the Airform membrane is designed, patterned, cut, seamed, and shipped to the dome builder, who attaches it to a ring foundation and inflates the membrane — often in front of the press. Did it fit? Is it the right shape? Can they continue construction or will the whole project be delayed?

The process is fraught with design challenges. The goal is to assemble flat fabrics into a three-dimensional air structure. For complex membranes, there are layers of contrasting problems of inflatablity versus constructability. There’s an art to this process.

Jack Boyt — Airform pioneer and my mentor — used to say, “You must cultivate a sufficient amount of paranoia.”

It was his mantra. No system was perfect. It can always be improved.

Jack would design an Airform at a drafting table with a programmable calculator, architectural scale, and a french curve. He carefully laid out each design by hand. It was a detailed process with checks and double checks he followed to reduce errors. Thirty-two years ago, I sat at his table, learning his craft, and gained an appreciation of this checklist — and his mantra.

He taught me the art of membrane design.

The Eye of the Storm Monolithic Dome home was the first prolate ellipsoid membrane pattern I designed — using VersaCAD on an old IBM PC.

My first custom Monolithic Dome Airform was for the Eye of the Storm, a Monolithic Dome home on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. Instead of a french curve on a drafting table, I used a CAD program, but the design steps were the same ones I learned from Jack.

After inflating the membrane, the dome builder called to say it was within one inch of the target dimensions. I was elated.

We’ve manufactured hundreds and hundreds of membranes. Murphy’s law is always trying to bite us. We’ve added vital steps to make Murphy shut up including customer-approved shop drawings, fabric testing, better seaming equipment, seam strength tests, automated cutting tools, and pre/post inspections.

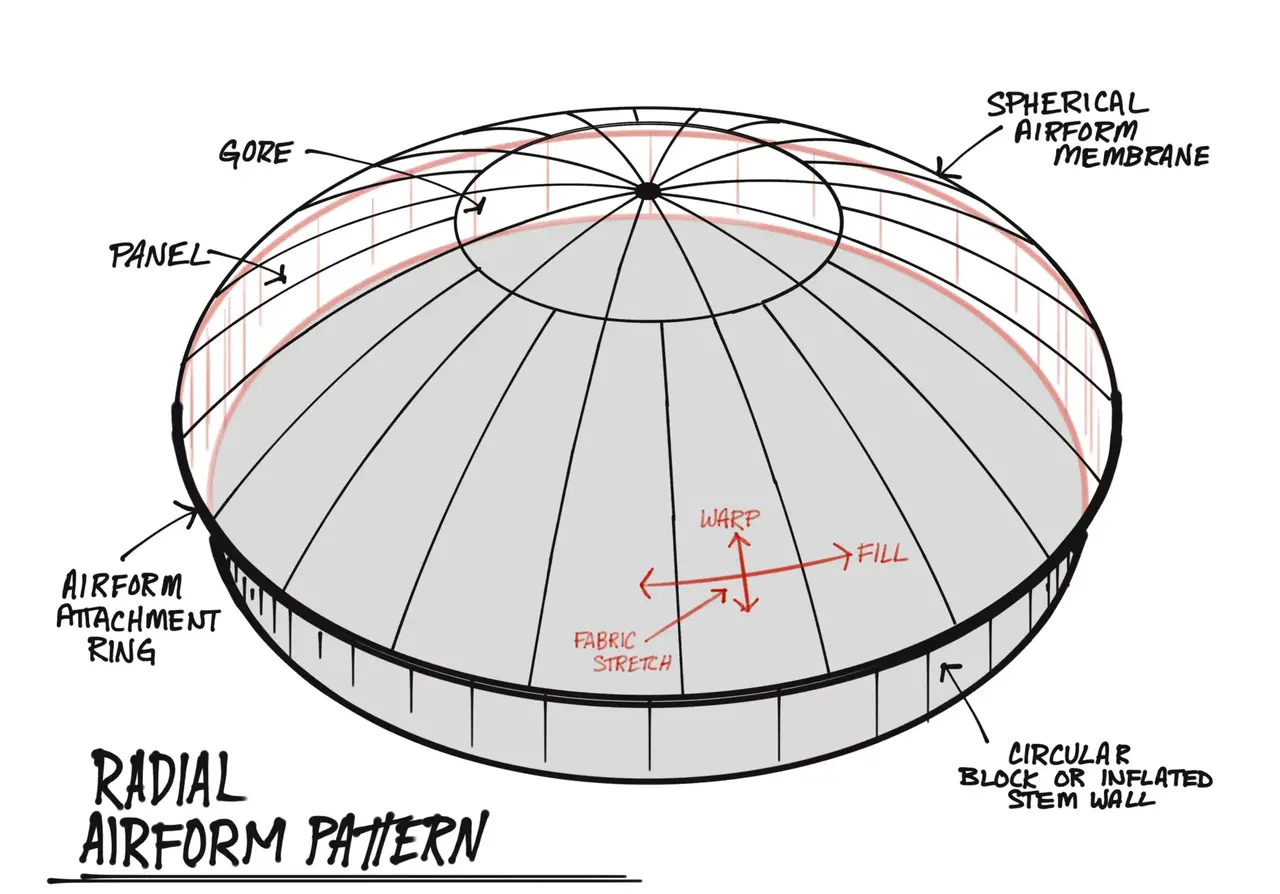

A sketch of how the original Airform membranes are patterned based on a radial gore design. Jack Boyt pioneered this design in the early 1980s. The radial design is best for hemisphere or silo-shaped Monolithic Domes.

There is another area where we reduce errors — custom software.

Jack’s original BASIC software was the base we built on. I’ve written multiple iterations and improvements over the years. I’ve also written from scratch software to assist Airform membrane augmentations and my new Transverse Airform Pattern.

Why would we write custom software?

A prominent executive once told me there is “software written to solve every problem.”

Oooh. That’s naive, at best. Tragically misinformed at worst. Software isn’t magic. It’s just a tool.

Yes, there are general-purpose tools for membrane design. We use several applications every time we design a custom Airform, but it’s far from automatic. We must follow many steps, accurately and faithfully, to pattern a membrane.

Like that wedding dress, you cannot allow a mistake to slip through or the dress will be ruined — and you won’t hear about it until the wedding day — well, inflation day.

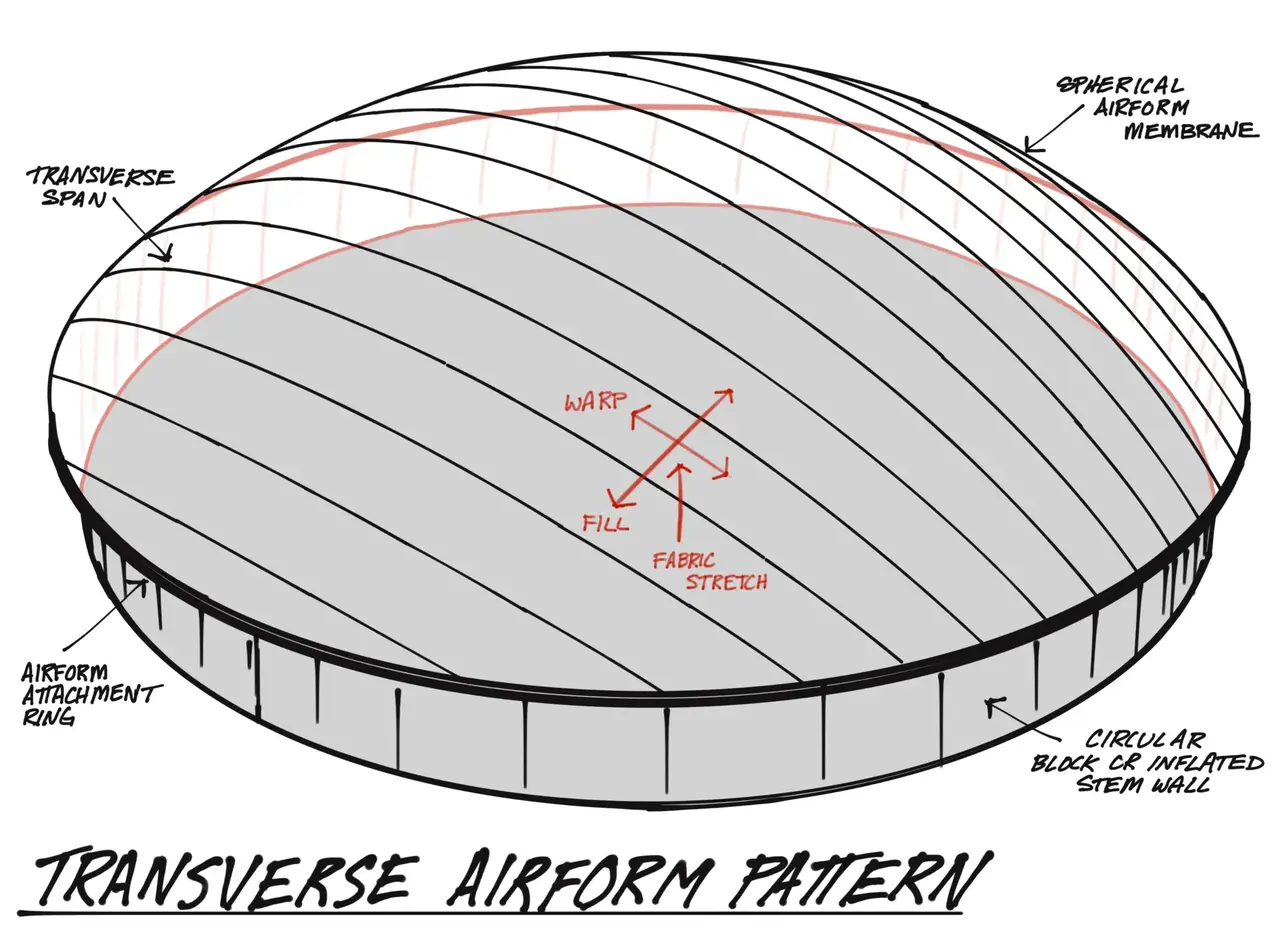

A sketch based on the Transverse Airform membrane pattern for Drummond, Oklahoma. It seems simple to lay the gore pattern sideways, but the fabric stretches more across the width (fill) of the fabric than the length (warp). The pattern is “pre-shrunk” — more across the width, less down the length — so when it inflates, it stretches to the proper shape.

Sometimes, the best tool for the job is the one you create yourself. Crescent is a custom application I developed to pattern ellipsoid Airform membranes — like the one for Eye of the Storm.

Yes, I can do these designs using CAD and tension membrane software, but why? An ellipsoid is a consistent shape. The technique can be automated. With only a few dimensions — the elliptical base width and length plus the membrane height — Crescent would distill everything we’ve learned in ellipsoid membrane design into a repeatable program.

When an Airform is inflated, it stretches. A 120-foot diameter dome membrane may need over four feet of material “removed” when manufactured so it stretches four feet into the proper size when it’s inflated.

In essence, the program has to predict a shape and shrink it into a fabric pattern. We wouldn’t need the software if we didn’t have to worry about tension. It’s hard enough to calculate a spherical form where tension and fabric stretch are uniform. An ellipsoid membrane’s tension and stretch are variable across the whole shape.

I had to break the problem into parts — calculating the overall shape, dividing it into gore patterns, intersecting the gores with the foundation, adjusting the fabric pattern for predicted tension, and adjusting again for tension as the fabric nears the foundation.

It took six, intense, weeks to write. The finished Crescent application analyzes over 10,000 data points across the ellipsoid surface and transposes that information into a set of unique fabric spans. The output is imported directly into CAD software to add seams, and marks, and prepare it for the automated cutting machine.

The first patterns generated by Crescent were for the two Monolithic Dome tornado shelters in Tupelo, Mississippi. These are two, elliptically shaped Monolithic Domes built on top elliptical block stem walls — 104 feet by 83.5 feet.

The dress fit. The membranes worked as expected and now we have a new tool for quickly and accurately patterning ellipsoid membranes.

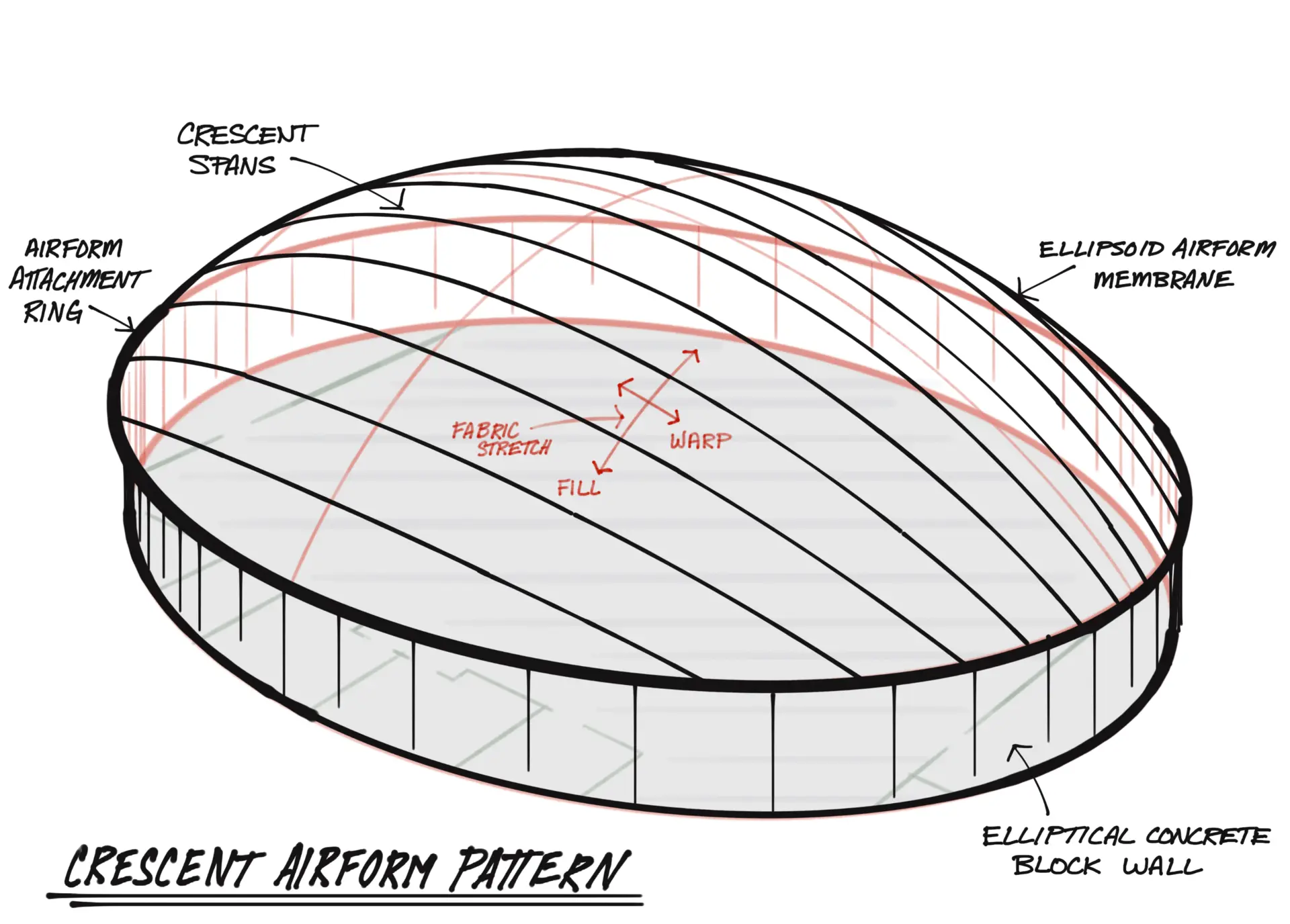

A sketch of the first Crescent Airform membrane for the storm shelters in Tupelo, Mississippi. The Crescent application analyzes over 10,000 points across the membrane, calculates variable tension across the surface, and compensates the fabric pattern so it will inflate to the proper shape.